Cognitive Toolkit

Our mind comes with strong biases that we inherit from our biology and society. My plan is to understand these biases and learn how to identify and counter them in my own life. I am slowly revising this list and adding references and examples. The numbering system is from the original list by Peter McIntyre [1].

(1) Signalling/countersignalling

The idea that an action conveys information to someone about the actor. Buying an expensive wedding ring conveys that you don’t think you’re about to run off immediately after the wedding (lest you lose three months of your salary). Countersignalling is when the information you’re trying to signal is so obvious that you need not have signalled in the first place. For instance, Warren Buffett doesn’t need to drive around in a Ferrari to signal how rich he is – everybody already knows that – and not driving around in a Ferrari differentiates him from the plebs that do need to drive one. Note: Buffett still lives in his house in Omaha that cost $31,000 back in 1958, despite being worth billions, but possibly for reasons other than countersignalling.

(2) Nudge

The manner in which choices are presented to a target audience can have dramatic effects on their chosen action – even without changing the incentives which might typically motivate an individual to make a given choice. […] The tax office can write letters saying that 90% of people who work the same job as you have completed their tax return already. Your electricity company can install an electricity meter which constantly reminds you how many watts you’re chewing through at a given time. Male urinals are sometimes made with a small and shoddy picture of a housefly in the centre of them as a target to reduce puddles.

(3) Marginal thinking

What are extra resources worth? If you have no bananas, and you get a banana, it’s probably worth more to you than if you already had one million bananas and you get an extra. This is an important concept because it might lead to the realisation that not all the bananas hold the same value to you. Slightly less trivially, what matters with your charitable donation is what happens with that donation, not the average of what the charity achieves. Extra donations to distribute bed nets could do more once there are already the distribution lines established, so it could achieve more. Conversely, it might be already distributing at capacity, and extra donations buy bed nets for $10 instead of $5. […]

(4) System 1 & System 2 thinking

When we’re making decisions, we use two different systems. System 1 is fast and subconscious, often described as our ‘gut feeling’. It has an edge in social situations or when time is a limiting factor. System 2 is slower and more methodical, better with models and numbers, and deliberate.

(5) Comparative vs. absolute advantage

If you are better than me at earning an income from your job and cleaning the house, you have an absolute advantage in both these activities. Does that mean that both of us are better off if you do both? Not necessarily. Suppose you earn $100/hour at work, 10 times more than my $10/hour and further that you clean the house approximately twice as fast as I do. Of these two jobs, I’m ‘least bad’ at cleaning the house, so it might be (depending on the social costs that this arrangement incurs) that both of us would be better off if you paid me $25 an hour to clean your house. Generally, people should do the action that they’re the least bad at, thus working to their comparative advantage.

(6) Efficient market hypothesis

There are many people approximately as clever as you who value approximately the same things you do. It’s unlikely you’ll be walking down the street and stumble on $100’000 sitting on the ground which no one else has picked up. In the same way, it’s unlikely you’ll be able to choose a company on the stock market that will do 100 times better than the average company which no one else has already found and invested in (driving the cost of parts of the company (shares) up). This is the same reason why you might have a hard time finding a car park that is (i) free, (ii) right next to work, and (iii) somewhere you can park in all day. Even though such car parks do exist, over time word gets out, and they are occupied in the short term or monetised in the long term. Everything is a market. Thus, when taking the efficient market hypothesis into account, you should

- look for the things you value in places that other people have systematically failed to look, and

- think that if something looks too good to be true, it probably is.

(7) Illusion of transparency

We tend to overestimate how much our mental state is known by others, a fact not helped by the ambiguity of the English language. “Elizabeth Newton created a simple test that she regarded as an illustration of the phenomenon. She would tap out a well-known song, such as “Happy Birthday” or the national anthem, with her finger and have the test subject guess the song. People usually estimate that the song will be guessed correctly in about 50 percent of the tests, but only 3 percent pick the correct song. The tapper can hear every note and the lyrics in his or her head; however, the observer, with no access to what the tapper is thinking, only hears a rhythmic tapping.” – Wiki. This phenomenon applies equally well to explanations of novel concepts and the interpretation of emotional states.

(8) Opportunity cost

When we choose to take one option, we are implicitly not taking another. If you only have enough room for one meal and your favourite is the Pad Thai, you choose it. But this means you can’t also get the Massaman curry (your second favourite). Economists call this your opportunity cost — your choice minus the benefits of the next best alternative. Opportunity costs are everywhere and form a critical part of decision making. If you’re not donating to the very best charity, you’re not helping others as much as possible. Furthermore, if you don’t spend your time in the best way possible, that is coming at a cost.

(9) Cognitive biases

These are systematic flaws in how we think. We don’t look for informationthat proves us wrong. We estimate that events we can easily recall (perhaps because they happened more recently, or frequently appear in the media) are more likely to occur than they are. We’re overconfident. Particularly relative to our level of expertise. And a whole bunch more. The plot thickens: it’s only our friends and colleagues who are biased. (Author’s caution: don’t become fallacy (wo)man).

(10) Heuristics

We use rules of thumb to make decisions under conditions of uncertainty (which turns out to be almost every single decision we make). This is both a blessing and a curse. It’s quicker, useful when we don’t have much information we could deal with explicitly. But also by its nature requires us to make generalisations that might not turn out to be true. It pays to notice that we are using them because they can be wrong.

(11) Counterfactual reasoning

What might have happened otherwise? You could push the paramedic out of the way and do the CPR yourself, but you’ll likely do a worse job. So even if you stop the patient from dying, your (counterfactual) impact is likely small, if not negative. Doctors wanting to make a big difference will do more good if they travel to a developing country where their patients might not have received quality healthcare if not for them.

(12) Bayesian reasoning

Assigning a probability before an event, receiving evidence, and updating the probability you assigned. This is beneficial insofar as it forces us to think probabilistically. Moreover, it allows us to account for competing evidence and promotes a nuanced view, thus avoiding a simplistic black and white application of ‘good and bad’ outcomes.

(13) Expected value

The probability of each outcome multiplied by the value of each outcome. For example, a 50% chance of winning $100 is worth $50 to you, and you should be willing to invest up to $50 for a chance to win (but no more). Applied example: If you have two mutually exclusive ways of helping people, should you take the 10% chance of helping 1 billion people, or the 90% chance at helping 1 million (an equal amount as the billion, and holding all else equal)? Without using expected value, this is a nearly impossible question to evaluate.

(14) Time value of money

We’d prefer to have $100 today than tomorrow, or in a year’s time. In a real sense, this implies that money today is worth more than money in the future. This preference comes from the opportunities we have to invest it at (say) 5% interest and gain $5 in that year. How much less you’d be willing to receive now than in a year, is the discount rate (which is 5% in this example).

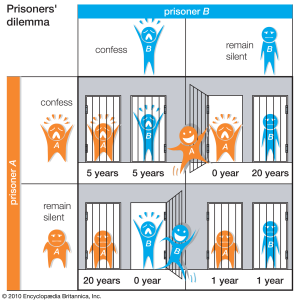

(15) Prisoner’s dilemma/ Tragedy of the commons

A problem in game theory that explains a lot of real world problems. In this situation, there are two players choosing between cooperating and not cooperating. You both do well if you both cooperate. But if you don’t cooperate while the other player tries to cooperate, you do even better. If both of you don’t cooperate then neither of you do well. But if you’re the chump who tries to cooperate while the other player doesn’t, you get screwed worst of all. Examples of this include countries individually benefitting economically from not limiting their carbon emissions, to everyone’s detriment; athletes using performance enhancing drugs to be more individually competitive, when all athletes would be worse off if everyone did it; everyone in society benefits from paying taxes to get roads, but each citizen would rather have the road and not pay taxes herself; etc..

(16) Revealed preferences

Talk is cheap, and our actions reveal more about our preferences than we’d like to believe. For instance, although I might say that Marmite is my favourite spread to put on toast, I actually buy Vegemite (#justaustralianthings). As such, my actions revealwhat I really prefer. In another example, while Tesla might survey thousands of Australians, of which 60% say they’d pay extra for a greener car, when the car actually becomes available, only 10% follow through with their purchase.

(17) Typical mind fallacy

The mistaken belief that others are having the same mental experiences that we are. As the links show, the differences go surprisingly far. Detailed questionnaires have shown that when some people ‘see’ a zebra in their mind’s eye, they’re simply recalling the idea of a zebra, whilst others can count the stripes!

(18) The value of your time

You could use your time to earn more money, or do something else that you value. Even if driving to the other side of town saves you $10 on groceries, if it takes you an extra hour, you’re implicitly valuing your free time at $10 per hour. This might be a good deal if you only earn $6 an hour with the company you started after seeing the story of “This One Single Mom Makes $1000 Per Hour – Google HATES Her”. On the other hand if your friend Grace can convert her free time into $50 an hour at work, then for her driving the extra hour is a poor use of time. What’s more, if both Grace and yourself are volunteering alongside each other in a soup kitchen when you’d be happy to work there for $10 an hour, Grace should consider working instead, donating the money she earns, and employing 5 people like you to run the kitchen per hour she is at work.

(19) Fundamental attribution error

Attributing others’ actions to their personality, but your actions to your situation. You see someone kick the vending machine and assume it must be because they are an angry person. But when you kick the vending machine, it’s because you were hot and thirsty, your boss is an asshole, and the vending machine stole your last goddam dollar.

(20) Aumann’s agreement theorem

If two rational agents disagree when they both have exactly the same information, one of them must be wrong. The ‘same information’ qualifier is crucial; very often disagreement is due to differences in information, not failure of rationality. So you should take disagreement seriously if you have reason to believe the other person has significant information that you don’t.

(21) Bikeshedding

Substituting a hard and important problem for an easy and inconsequential one. When designing a nuclear plant, Parkinson observed that the committee dedicated a disproportionate amount of time to designing the bikeshed – which materials should it be made of, where should it be located etc. These are the kind of questions that everyone is clever enough to contribute to, and where everyone likely wants to have their opinions heard. Unfortunately, these might be discussed at the cost of some of crucial detail, like how to prevent the power plant from killing everyone.

(22) Meme

The social equivalent of a gene, except instead of encoding proteins, they represent rituals, behaviours, and ideas. They self-replicate (when they’re passed from one person to another), mutate, and some are selected for in a population – these are the ones that get transmitted. Like selfish genes, the most useful memes don’t necessarily get reproduced. Rather, it is those that are most likely to have a trait that is selected for. Memes are interesting because of the predictions they allow you to make. For instance, there should be few major social movements in society that don’t have the meme “find (or create) other like-minded people to join the movement”.

(23) Algernon’s Law

IQ is nearly impossible to improve in healthy people without tradeoffs. If we could get smarter by a simple mechanism, like upregulating acetylcholine, which had no negative side effects (in the ancestral environment), then perhaps evolution would have upregulated acetylcholine already. We could equate this with the ‘efficient market hypothesis’ of improving brain function.

(24) Social intuitionism

Moral judgements are made predominantly on the basis of intuition, which is followed by rationalisation. For example, slavery was previously a social norm and thought to be acceptable. When asked a question (“is slavery good?”), proponents of slavery introspected an answer (“yes”), and confabulated a reason (“because they’re not actually human” or similar atrocious falsehoods). As this example shows, blind faith in our intuitions can be harmful and counterproductive, because they can be easily corrupted by immoral social norms. It wasn’t just that proponents of slavery got the wrong answer: they had — and we still have — the wrong process.

(25) Apophenia

The natural tendency of humans to see patterns in random noise. E.g. hearing satanic messages when playing songs in reverse.

(26) Goodhart’s law/ Campbell’s law

What gets measured, gets managed (and then fails to be a good measure of what it was originally intended for). If we use GDP as a measure of prosperity of a nation, and there are incentives to show that prosperity is increasing, then nations could ‘hack’ this metric. In turn, this may raise GDP while failing to improve the living conditions in the country.

(27) Moral licensing

Doing less good after you feel like you’ve done some good. After donating to charity in the morning, we’re less likely to hold the door open for someone in the afternoon.

(28) Chesterton’s fence

If you don’t see a purpose for a fence, don’t pull it down, lest you be run over by an angry bull which was behind a tree. If you can’t see the purpose of a social norm, like whether there is any value to having family unit, you shouldn’t ignore it without having thought hard about why it is there. Asking people who endorse the family unit why it’s important and noticing their reasoning is flawed often isn’t good enough either.

(29) Peltzman effect

Taking more risks when you feel more safe. When seatbelts were first introduced, motorists actually drove faster and closer to the car in front of them.

(30) Semmelweis reflex

Not evaluating evidence on the basis of its merits and instead rejecting it because it contradicts existing norms, beliefs and paradigms. Similar to the status quo bias (which one might choose to combat with the reversal test).

(31) Bateman’s principle

The most sexually selective sex will be that which has the most costs from rearing the offspring. In humans, women have more costs associated with raising offspring (maternal mortality, breastfeeding, rearing) and are the more selective sex. In seahorses, the opposite is true: male seahorses carry the offspring in their pouch, and are more selective with those they choose to mate with.

(32) Hawthorne effect

People react differently when they know they are being observed.

(33) Bulverism

Dismissing a claim on the basis of how the opponent got there, rather than a reasoned rebuttal. For example, “but you’re just biased!” or “of course you’d believe that, you’re scared of the alternative.”

(34) Flynn effect

IQ has increased by 3 points per decade since around the 1930s. It is hotly debated why this is happening, and whether the trend will continue.

(35) Schelling point

A natural point that people will converge upon independently. For instance, if you and I have to meet in Sydney on a particular day, and we don’t know when or where, we might go to where we normally meet, or fall back on meeting at the Opera House at 12PM. This is an important effect in situations where coordination is essential but explicit discussion is difficult. Furthermore, participants may not even realise it’s happening. For example, “I don’t want to live in a society where genetic enhancement of children increases the gap between the rich and poor. Unfortunately, there’s no clear place at which to say ‘wait, we’re about to reach that society now, let’s stop enhancement!’ Perhaps my comrades and I should instead object against any genetic manipulation at all, including selecting for embryos without cystic fibrosis (even if we wouldn’t mind that particular selection occurring).”

(36) Local vs global optima

See the carefully crafted image by yours truly below. In short, you might need to make things worse in order to get to a global optimum – the best possible place to be. If you want to earn more, you might have to sacrifice the number of hours you can work in the short term in order to take a course which will allow you to increase your income in the future.

(37) Anthropic principle

You are given a sleeping pill which will wake you up twice if heads, and once if tails. You wake up. What is the chance that today is the day you wake up twice? Similarly, what is the chance that we’re in one of the only universes that is capable of supporting life?

(38) Arbitrage

Taking advantage of different prices between markets for the same products.

(39) Chaos theory

“Chaos: When the present determines the future, but the approximate present does not approximately determine the future.”

(40) Ingroup and outgroup psychology

This doesn’t just explain phenomena like xenophobia, but also the left-right political divide. Our circle of concern is probably expanding over time.

(41) Red Queen hypothesis

Organisms need to be constantly evolving to keep up with the offenses and defenses of their predators and prey, respectively. This is probably the effect we should thank for the existence of sex.

(42) Schelling’s segregation

Even when groups only have a mild preference to be around others with a similar characteristic – say, a preference for playing baseball – neighbourhoods will segregate on this basis.

(43) Pareto improvement

A change that makes at least one person better off, without making anyone worse off.

(44) Occam’s razor/ law of parsimony

among competing hypotheses, the one with the fewest assumptions should be selected.

(45) Regression toward the mean

If you get an extreme result (in a normal distribution) once, additional results are likely to be closer to the average selection. If one trial suggests that health supplement x is amazingly better than all the others, you shouldn’t put all your faith in that result.

(46) Cognitive dissonance

Holding two conflicting beliefs causes us to feel slightly uncomfortable, and to reject (at least) one of them. For instance, holding the belief that science is a useful way to discover the truth would conflict with another belief that vaccines cause autism. In you held both of these beliefs, one would have to be discarded.

(47) Coefficient of determination

How well a model fits or explains data (i.e. how much of the variance it explains).

(48) Godwin’s Law

As an online discussion grows longer, the probability of a comparison involving Nazis or Hitler approaches 1. At this point, all hope of meaningful conversation is lost, and the discussion must stop.

(49) Commitment and consistency

If people commit to an idea or goal, they are more likely to honour the commitment if establishing that idea or goal is consistent with their self-image. Even if the original incentive or motivation is removed after they have agreed, they will continue to honour the agreement. For example, once someone has committed themselves to a viewpoint in an argument, rarely do they change ‘sides’.

(50) Affective forecasting

Predicting how happy you will be in the future contingent upon some event or change is hard. We normally guess that the magnitude of the effect will be larger than it actually is, because 1) we’ve just been asked to think about that event, which makes it seem more important than it actually is in our everyday happiness, and 2) we underestimate our ability to adapt.

(51) Fermi calculation

(aka ‘back of the envelope calculation’) involves using a few guesses or known numbers to come to an educated guess about some value of interest. To illustrate, one could approximately calculate the number of piano tuners in Chicago by plugging a few estimates like population, percentage of houses with a piano, and piano tuner productivity into a calculation.

(52) Fermi’s paradox

Is the problem we confront when we run a Fermi calculation on the number of habitable planets in our galaxy and realise how weird it is that we seem to be alone. It leads to some interestingconclusions.

Look into

- Illusion of Knowledge – (similar to illusion of knowledge) when surrounding environment shares some expert knowledge, but one only believes to have it.

References

- “52 Concepts To Add To Your Cognitive Toolkit” by Peter McIntyre (provided the basis for my article)

- Hacker News comments on “Concepts for Your Cognitive Toolkit” (above) (many useful corrections)

on